It’s just past 2:30 on a Saturday afternoon in Riquewihr, France. One by one, the two apprentices and two junior cooks arrive in the kitchen and start their daily routine. Steve lights the oven. Thomas starts bringing today’s vegetables from the walk-in box next door. Guillaume sets out the cutting boards at each of the five work stations in the kitchen. Jurgens sets some water to boil on the stove to cook the lobsters. It’s a routine they execute with efficiency and speed. By the time the senior cooks Jacky and Sebastian arrive, the daily grind is well underway. As each cook enters the kitchen, there’s a bonjour and a handshake for those already at work. If a cook’s right hand is dirty, the new person shakes his wrist instead.

An hour or so later, Rémy, the pastry chef, cheerfully saunters in and greets one and all. He comes later because at the end of the shift, the others will be finished with all their tasks while he is still preparing desserts for the last remaining guests in the restaurant. Some time during this period, Chef François Keiner will come downstairs from his living quarters above the kitchen and make sure that all is proceeding appropriately towards the evening’s meal service at Auberge du Schœnenbourg, a Michelin one-star restaurant in the heart of Alsacian wine country.

Into this ordered routine I come like the proverbial bull in a china shop — clumsy, ill at ease, and liable to bring everything crashing down at any moment. I’m at the restaurant for a ten-day stage. (A stage is a French tradition where someone pays for the opportunity to work in a kitchen for the experience and to learn directly from the chef.) This isn’t the first time I’ve spent an extended period in a French kitchen, but it still takes a while to enter into the kitchen’s unique routine and interact with its unique cast of players. Also, these are professionals and I’m just someone with a strong interest who strangely considers this a good way to spend a vacation. In Riquewihr, except for the Chef, I’m twice as old as any of the other workers — a difference I’m keenly aware. But, I have no way of knowing if the cooks are bothered by the age difference since I’m not conversant in French and they know only a few words of English.

This is the first time I’ve entered this restaurant, although I am somewhat familiar with the area, having traveled through it a number of times in the past. A friend referred me to the Chef. When I learned that I was coming to France for another purpose a couple of months ago, I simply called the Chef and asked if I could do a stage with him. Up to our first meeting, we have had only a couple of short telephone calls. He knows little about me and I know less about him! When I arrived at the restaurant at about noon, after a four-hour car ride, I found it locked and dark. It’s not until now that I learn the restaurant is only open evenings, except Sundays. I checked into the hotel and went over to the restaurant periodically until I found the kitchen occupied. After I finally made contact with the Chef, we decided that I will start right away. I returned to the hotel to change into my white chef’s jacket, and now my adventure begins…

The kitchen is small. When the dishwasher arrives, there’s a total of ten of us occupying a space ideally filled by half our number. Instead of the large, custom-made, two-sided range I’m used to at other Michelin-starred restaurants, this one here seems like it would be incapable of producing enough meals for the sixty customers the Auberge serves when it is completely full. Equipment is placed wherever there’s a little extra space. Most of the storage is in the basement or in another large room across the alley behind the restaurant. The most common word heard in the kitchen is “pardon.” It is impossible to move freely without having to zigzag between the bodies at work. When things start to hustle later in the shift, there’s more body contact and fewer pleasantries.

During the period from when they arrive until a few minutes before six o’clock when they break for dinner, the staff concentrates on mise en place, the preparation of the food stuffs that will be needed for dinner service. Much of the preparation is for items that will be needed a few days from now, rather than just for tonight. Sometimes this is because it is more convenient to do prep for multiple days at a time, sometimes because someone just needs something to do.

© 2001, 2014 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

One of my first jobs is shucking scallops. As I am to learn shortly, fresh scallops are purchased three or four times a week and since they are alive, they must be shucked the day they arrive at the restaurant. Like many of the tasks I will do for the next couple of weeks, I’m shown the method used at the Auberge to shuck scallops, and I use that method rather than how I’ve learned elsewhere. After all, I’m here to learn and their methods may be better than the ones I’ve learned in the past!

On my first day in the kitchen I’m handed a 12-kg box of scallops to shuck. I will become really familiar with these 12-kg boxes by the time my stage is over. These scallops also provide the first chance I have to embarrass myself in front of my fellow workers. A sharp edge on the shell of the last scallop I shuck from the box tears a chunk of skin out of the thumb on my left hand. It’s hard to look cool when you can’t stop the blood from flowing. One of the junior cooks takes me over to the supply cabinet filled with various bandages and applies an adhesive bandage to my injured thumb. After about five seconds the blood starts to flow from the bandage so I take charge and wrap my thumb tightly in tape. I figure that if the blood can’t flow to the cut, I’ll stop bleeding. It seems to work.

Each day there are certain daily tasks that someone will perform during mise en place. Although there are minor tweaks to the menu on an almost daily basis, the core of the menu is seasonal. This means that each day there is an informal inventory of all the individual elements required to complete every dish. Even with the modern day conveniences of vacuum packing and freezing, some items have to be prepped almost daily.

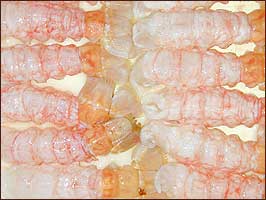

Lobsters seem to be a daily visitor to the kitchen. During my stage, four to six lobsters are cooked each day at the start of the shift. Fish are filet and portioned. The current menu includes sandre (a freshwater pike-perch), omble chevalier (a type of salmon trout), rouget, and salmon. Langoustines are separated into heads and tails — the tails are shelled and the heads become langoustine bisque. Various univalves (shellfish) are cooked and shelled.

Periodically, whole beef tenderloins are carried into the kitchen. The tenderloins are trimmed thoroughly and cut into portions. Whole legs of lamb are boned and the meat formed into appropriate shapes for roasting. Whole ducks are partially roasted. The breasts are boned and sliced crosswise into thick, wedge-shaped slices. The slices are arranged with caramelized apples in between, seasoned with ginger and honey, and vacuum packed. For service, the whole package is carefully opened onto a baking sheet and the contents heated in the oven. The duck legs are used for staff meals and the carcass for sauces. Pigeons arrive plucked, but otherwise intact. After prep, all that is left are the skin, the meat, the leg bone, and the upper wing bone — all trussed together with a couple of toothpicks.

Every couple of days, a half a dozen foie gras de canard are cleaned and prepped for a couple of dishes. The methods used here are different from what I’ve seen or read about elsewhere. The chef demonstrated for me the way he wanted the livers to be prepped, but I notice that the other cooks each have their own variation of his methods. I see a lot of this with other techniques, as well. The Chef says to do things one way, but when his back is turned, the staff reverts to whatever method they prefer. One of the few times I see the Chef raise his voice is when he catches a cook doing something different from what he has specifically instructed. One day when we are discussing his manpower layout in the kitchen he confides that one of his biggest problems is getting the cooks to do things the way he wants them done, rather than the way they want to do them. He says that there isn’t the discipline in the kitchen today as there was in the past.

© 2001, 2014 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

Throughout the preparation time, there’re lots of vegetables to be peeled and cut. There’s dicing — mirepoix (10 mm), macédoine (5 mm), and brunoise (2 mm). There’s shredding — julienne (2 mm). And there’s tourner where carrots, turnips, and zucchini are “turned” into football-shaped morsels. The vegetables being used for stocks and sauces are cut in mirepoix. The vegetables that will be cooked and puréed will be cut in macédoine. The vegetables cut in brunoise — red and green bell peppers, carrots, celery root, and zucchini — will be cooked and used for garnish called brunoise de légumes. A lot of carrots get peeled, a lot of peas get shucked.

Wild mushrooms are in abundance at the produce market and every variety is represented in the kitchen here. All the mushrooms are cleaned, trimmed, and sometimes peeled. Then they are blanched in boiling water for a couple of minutes. The Chef says that doing so seals the mushroom so they don’t release a lot of water when they are cooked. Most of the mushrooms will be fried lightly in butter and used for garnish, although some will be used for other preparations. Only once did I see champignons de Paris — common white mushrooms — in the kitchen and I don’t know into which dish they went.

The spinach has coarse ribs and almost looks more like chard than spinach. It arrives in the kitchen, loose and unwashed, in a 10-kg crate. The ribs are separated from the leaves and tossed out. Most of the spinach appears to be cooked in butter with some garlic cloves. It is then cooled and used as part of other preparations.

Tomatoes are blanched and peeled. Usually, a whole case is prepped at once. What is not immediately needed is stored in the walk-in box for a few days. Most of the tomatoes are eventually halved, seeded, and oven dried. These are used as a garnish. Some make their way into other preparations. While I’m there, all the tomatoes I see are what in the U.S. are sold as “cluster tomatoes.” In France they are called tomates en grape. There’re usually 65 to 70 tomatoes in a crate.

Since this is asparagus season in the Alsace, a few of these make it onto the menu. In this case, these are very thin, immature stalks sold neatly packaged in plastic boxes. During prep, the leaves are removed and the ends trimmed. These are blanched in chicken stock — made from powdered chicken stock base — along with peas, carrots, cauliflower, broccoli, snow peas, and Chinese cabbage. Each is blanched separately. The blanched vegetables are mixed with a combination of chicken stock, melted butter, salt, and pepper. They are then drained and divided into serving portions, i.e., one carrot, one piece of broccoli, one spear of asparagus, etc., and placed decoratively in disposable plastic containers. At service they are simply placed on the plate and reheated.

One of the standard side dishes they serve here is puréed celery root. The root is peeled and cut into a large mirepoix. The cubes are blanched until tender. They’re then put into a food processor with some cream and processed. The purée is forced through a sieve to further smooth it out. Some finely minced truffles are added to the mixture before it is served.

© 2001, 2014 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

One of the seafood dishes served at the Auberge consists of langoustine tails and vegetables wrapped in a sheet of pasta. The dish is called ravioli ouvert aux langoustines, coquillages et légumes aromatiques. The vegetable portion consists of julienned, roasted, and peeled green and red peppers; pitted and sliced black and green olives; julienned and blanched fennel; julienned and blanched zucchini skin; peeled and halved garlic; julienned pimento; julienned and blanched celery root; peeled, shredded, and pan-fried onions; and a bouquet garni consisting of basil and thyme. The vegetables are mixed with olive oil; seasoned with saffron, salt, and pepper; and set aside to macerate. It takes one cook a substantial portion of the prep period to prepare all these vegetables.

And then there’s topinambours — Jerusalem artichokes. These inexpensive tubers are bought by the case and someone has to peel them. They oxidize quickly and require the use of a lot of water when peeling; all in all, a fairly time consuming task because of their irregular shapes. By the time a case is peeled, your hands are as black as if you had polished shoes all day. Once peeled, they are attacked with a 14-mm melon baller and turned into cute, little balls of gas producing starch. The artichoke balls will eventually be drained and sautéed in a little butter, salt, and pepper. A sprig of thyme and some minced orange zest will be added, along with a little fond de veau to moisten the pan. The pan is covered and the heat reduced to simmer. When the artichoke balls are tender, the dish is finished with a little butter. The pieces of artichoke not turned into balls are saved and used for staff meals. (What joy!)

Herbs — typically dill, chervil, parsley, and tarragon while I’m visiting the kitchen — are used for both flavoring and decoration. These come into the kitchen in large bunches, often with their roots and dirt. The leaves are stripped from the stems and refrigerated in large canning jars with moist paper on the bottom.

One day, the Chef obtained some fingerlings from a trout farm. These fish are two to three inches long. They’re being prepared as part of the amuse-bouche. One of the apprentices was given the job of cleaning them, and he invited me to help. When he saw that I was apparently having more fun at the task them he was, he walked away and left the remainder for my entertainment. Two hundred fish later, I was done.

© 2001, 2014 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

It’s a few minutes before six o’clock and it’s time for the staff to eat dinner. One of the junior cooks or the apprentices have been preparing the meal for the last hour or so. I learn that the first sign that dinner is about to be served is when a couple of plates are assembled and sent upstairs to the Chef and his wife. The cooks remove their aprons, grab the pots of food, and head down into the basement to the staff dining room. The room is crowded with a large wooden table covered with a red oilcloth. For seating there are plastic patio chairs.

There’s a hierarchy here. Jacky, one of the senior cooks, always sits at the head of the table. On days that he is not working, his place remains empty. Sebastian, the other senior cook sits to his right. Rémy, the pastry chef sits to his left. To Rémy’s left are the two junior cooks. One of the apprentices occupies the other end of the table and the last apprentice sits opposite the junior cooks. This places the apprentices farthest from the door. Everyday, each cook sits in the same seat. No one explained any of this to me, so on the first day I sat in Sebastian’s seat. He didn’t say anything, but I figured that something was amiss, so the next day I made sure I was the last person to reach the room and took the empty chair, which was to Sebastian’s right.

Occasionally, one of the chef du rangs — one always arrives early to set up the dining room — will have dinner along with the cooks. Most of the time it’s Babette. On these occasions I move one seat to my right and she sits between Sebastian and me. She never eats the same meals that the rest of us eat — her meals often look like they’ve been brought from home. Also, she always brings a newspaper which she reads when she is finished eating — ignoring everyone else.

The meals that the staff wolfs down are not haute cuisine. One night there was grilled liver with corkscrew pasta and gravy. Another night the meal consisted of meat scraps prepared like steak, fried potatoes, and some mixed vegetables. The following night the dinner was baked rabbit with rice and vegetable soup. One meal was oeuf à cheval — a hamburger with a fried egg on top. This was served with mashed potatoes and gravy, plus leftover soup from the previous night. The hamburger was tender and cooked perfectly, but lacking in taste. It was made from the trimmings of filets and tenderloins and lacked fat. The following night’s meal started with the same vegetable soup as on other nights. This was followed by boiled potatoes, deep-fried grass shrimp (you eat the whole shrimp), some sort of fish, and (not so) hard-boiled eggs with garlic mayonnaise. I didn’t feel too well after this meal. Meals are accompanied by bottled water and conclude with coffee.

Staff meals are a quiet affair. In some ways it seems as if the staff is beginning to mentally prepare themselves for work ahead, but everyone is probably just wishing they were someplace else. There’s not much conversation in the staff dining room, unless the pastry chef is there. He likes to talk and joke, but he can’t always keep the conversation going by himself.

Except for Thomas, everyone smokes. Some have their own cigarettes; some seem to perpetually be borrowing cigarettes from the others. Marlboro is the most popular brand smoked. By the time six-thirty arrives and we head back upstairs to the kitchen, the air in the room is thick with smoke and practically intolerable for a person like myself who is not used to smoke-filled rooms.

© 2001, 2014 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

After dinner, the pace in the kitchen quickens slightly. Unlike most of France, many of the patrons eating in the Alsace are coming from Germany or Switzerland. The dining room opens at seven and it’s not uncommon for some Germans or Swiss to show up early. The French arrive at eight, or even later. The dining room of the Auberge holds about 60 people. While I’m visiting, the restaurant is mostly slow. Business will pick up in mid-April and continue strong until the beginning of winter.

Sebastian starts to fill the empty cavities of the steam table that divides the hot station from the service area. Each night there’re six to eight containers of sauces that are filled and kept warm for use on the various dishes served by the Auberge. Some sauces are reheated from the previous night. For those where there were no or insufficient leftovers, fresh sauces are prepared. Some of these sauces started early in the day, but others are started after dinner. For the beef dishes there’s a sauce called sauce marchand de vin, for the duck dishes there’s one called sauce du canard, and so on. There’s a lemongrass sauce for use with some of the seafood dishes.

Sebastian also starts to cook some of the garnishes that seem to find their way onto most of the dishes. There are four types of garnishes prepared every day. All of the garnishes are deep-fried — leeks, salsify, Jerusalem artichokes, and herbs. The unpeeled salsify and artichokes are sliced very thinly on a meat slicer before being fried at 180 °C. The salsify is cut lengthwise while the artichokes are cut crosswise into rounds. The herbs are basil and flat-leaf parsley.

Some of the side dishes, such as the puréed celery root, are also prepared at this time and given a position on the steam table.

On some days the Chef is an active participant in the mise en place. If he hasn’t been around much before six, he is certainly present after the staff dinner. Unlike other chefs I’ve observed who act more as a combination of traffic cop and quality control inspector during meal service, Chef Keiner participates in all aspects of the preparation and service.

For service, the kitchen is divided into a number of areas. One of the apprentices assembles the amuse-bouche plates in a small area next to the pastry chef’s territory. He finishes the assembly up front where all the dishes are plated. A little closer to the front of the kitchen, Jacky assembles the entrées (first courses). If any cooking is required, he deftly weaves his way through the activity at the stove or the salamander to finish his dishes. Sebastian and the Chef concentrate on the main courses — working in the area between the stove and the steam table.

© 2001, 2014 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

The service process starts when one of the comis de salles announces, “deux amuse-bouche, s’il vous plait” — “two appetizer plates, please.” The apprentice shouts back “oui” — “yes,” and the process begins. A short time thereafter, one of the chef de rangs enters with the order and shouts it out or hands it to Sebastian or the Chef. Everyone in the kitchen responds in the affirmative.

Plates for the various entrées ordered are assembled with their garnishes and placed in a rack near the plating area to await their final assembly. Entrées that have no hot components are fully assembled and placed in a small refrigerator near the entrance to the dining room. When the hot components are ready, they are added to the plates and all the entrées for the entire table are sent to the dining room at once. All the plates are hand carried to the patrons. In some fine restaurants in France, the plates are covered with domes, put on a tray, and carried to the dining room by a comis de salle. Sometime later, a chef de rang will serve the plate to the table. With this method, it takes more time to serve a large table because one chef will only serve two dishes at a time. Also, if the comis isn’t careful when bringing the dishes from the kitchen, the sauce may get splashed around the plate and the assemblies may collapse. With the method use here at the Auberge, everyone at the table is served at once with plates that arrive looking like they did in the kitchen.

When the entrée plates are removed from the table, the kitchen is told to prepare the next course. Sometimes, this has already started because an ingredient requires a longer cooking time. Meats that are ready before final plating are stored in a covered, stainless steel box that usually sits on the heated portion of the plating area. The box has a perforated plate on the bottom so the meats don’t sit in their juices. Miraculously, without much obvious communication, the main plates come together and are sent to the dining room. During this time, the junior cooks provide support for some of the dishes or continue to do further mise en place.

The Chef says that he doesn’t have a sous-chef because it isn’t worth the expense. In the past, when he gets someone fully trained, they go to work at some other restaurant. With the money he saves by not having a sous-chef, he hires an extra cook instead. The apprentices work for two weeks and go to school for one week. One apprentice is in his first year at the Auberge, the other apprentice is in his second year. I asked if the first apprentice was having problems because everyone was always yelling at him. The Chef said that actually he has more potential — you yell at the ones with potential — you don’t waste the effort on those without it.

While all this activity is going on in the front of the kitchen, Rémy, the pastry chef, is busy working on various dessert components required for the evening. If the patrons have ordered one of the preset menus, Rémy is aware of the dessert requirements early in the service. Patrons ordering à la carte order their desserts at the end of their meal; so for these, he has less warning. His evening is divided between preparing the components he needs to assemble the various desserts on the menu and doing the actual assembly. After the other cooks send the last main course out to the dining room and start to clean the kitchen, Rémy will be busy in his area dealing with dessert orders.

Besides the desserts, which not everyone orders, each diner receives an “intermezzo” after their main course and mignardises with their coffee. The intermezzo is a “chocolate cappuccino.” The mignardises are a selection of small cookies, petit fours, and chocolate truffles. On each plate is one of each item for each diner.

As the evening winds on, Rémy starts assembling the diner’s desserts. The desserts at the Auberge when I’m there consist mainly of ice cream assemblies, although there is one soft-centered chocolate cake that must be prepared to order. Rémy is still sending desserts out to the guests when the other cooks finish cleaning the front of the kitchen and prepare to leave.

Finally, the last dessert is served, the lights are turned off, and the kitchen shuts down.

© 2001, 2014 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

The “chocolate cappuccino” consists of a bite-size chocolate coffee cup filled with coffee mousse and hazelnuts. At the time of serving, a creamy, coffee-flavored foam that resembles foamed milk and a straw made from dark and white chocolate is added to the ensemble. The cups started days in advance by spraying chocolate into the forms with a spray gun — actually a Wagner Power Painter. After the mousse is piped in, the cups are frozen. I had the pleasure of removing the frozen cups from their individual forms one evening. A single tray holds about 200 of these. Later, I helped make a new supply of forms. They are cut from 1-1/4 oz Solo cups — the type used for dispensing pills in a hospital!

© 2001 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

After the individual livers are divided into their two lobes, the lobes are cut into scallops for grilling. The odd pieces are saved for use in terrines. They are arranged in pairs of the same size. The pieces are allowed to come to room temperature so that they are more pliable. Cleaning is performed by teasing the ducts and vessels from the cut pieces with needle-nose pliers. The scallops are matched in pairs and wrapped tightly in plastic wrap and reformed. They are refrigerated until they firm up again. The pieces are then unwrapped and placed on a grill. They are then lightly smoked, re-wrapped, and put in the refrigerator or freezer until needed. When they cook fois gras at the Auberge they dust it with flour before they sauté it.

© 2001 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

For the leek garnish, the white portion of the leek is peeled one layer at a time and washed. Working in pairs where the width of the leaves are about the same, the leaves are rolled tightly from the bottom until the green is reached. This is trimmed off crosswise. The rolled leek leaves are then cut crosswise very thinly — after the ends are trimmed. It is important to have all the pieces cut the same thickness. These are fried in 150 °C oil until they just start to color. The whole batch is drained at once on absorbent paper. Using a two-prong meat fork, groups of leek are twisted into small bundles. These are held at room temperature for a few hours until needed.

© 2001 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

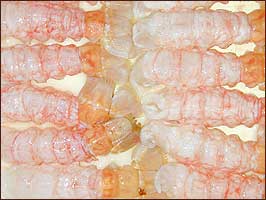

Extra care is required when shelling langoustines à la Auberge de Schœnenbourg — more care than I’ve seen elsewhere. The tail is carefully removed from the body by inserting your thumb under the body shell and removing the tail. Because the meat in the tail is fragile, the shell has to be supported as it is carefully broken, piece by piece. When the shell is squeezed crosswise, like a lobster, the bottom of the shell breaks. This is carefully removed allowing the tail to be lifted from the remaining shell. The sand vein is removed with a toothpick like a shrimp tail.

© 2001 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

For sauce citronelle, lemon grass, onions, leeks, and spring onion tops, plus a few leaves of mint are sweated in butter and olive oil. To this, white wine is added and reduced by half. Next, fumet de poisson (fish stock) is added and reduced by half. The solid ingredients are strain out and the final sauce is finished with cream.

© 2001 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

The Auberge serves a lobster entrée — feuillantines tièdes de homard en salade d’herbes, sauce fenouil — consisting of a disk of lobster with an underlayment of spinach that has been cooked in butter with some garlic. The lobsters are slightly bigger than a pound each. They are tied in pairs, tail-to-tail, belly-to-belly, with string. Odd ones have their tails tied to a small board. The purpose of this is to prevent the tails from curling inward during cooking. The “court bouillon” used for cooking the lobsters is just water with some vegetables, usually carrots and leek greens. After the water comes to a boil the lobsters are cooked for 6 minutes. When the lobsters are cool enough to handle, they’re taken apart and the meat is extracted. This starts with twisting the tail off the body. These critters are full of liquid and this becomes a fairly messy job. The tail is squeezed crosswise until the shell on the bottom breaks. The tail shell is then peeled off the tail and the tail meat set aside. (There are some sharp edges on these puppies!) The claws with the “arms” are twisted off the body and the body discarded. The arms are separated from the claws. A heavy pair of scissors is used to cut the arms open along their axis and the meat extracted and set aside. For the claws, the articulated portion is gently rotated and teased until it separates from the larger section. If you’re lucky, the meat pulls easily out of this section. If not, it can be gently extracted with a slow, steady pull. The large portion of the claw is then crushed with the blunt side of a large knife, and the shell peeled off the meat. At this point, there is a large piece of tail meat, four claw portions, and the meat from the arms. The tail is cleaned and cut into cross sections of the right thickness to fill the molding rings that already are lined with the spinach. The space in the ring are then attractively filled with the remaining lobster meat. The piece of meat from the larger part of the claw is saved to use as decoration. In total, four or five large lobsters are taken apart most days.

© 2001 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

The sauce marchand de vin starts by sweating a bunch of vegetables in oil and butter. In this case the vegetables are onions, leeks, spring onion tops, and shallots. Two large bottles of local red wine and some Madeira are added and then reduced by half. A rich fond de veau (veal stock) is added and the quantity reduced by half again. The final mixture is strained and finished with butter.

© 2001 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

They use a large variety of “wild” mushrooms here. These, of course, have to be sorted, cleaned, and prepared. Shiitakes, pleurotes, yellow chanterelles, girolles (another form of chanterelles), trompettes de mort (black chanterelles), pieds de moutons (hedgehog mushrooms), and a number of other varieties that I didn’t recognize were prepped. The shiitakes were bigger than normally found in the U.S. For these, the stems are just cut off and then the head cut into four pieces. The pleurotes were also different. They had a more symmetrical appearance than those sold in the U.S. as oyster mushrooms. For these, the stem is trimmed and the mushroom is once again cut into quarters. The pieds de mouton have gills that are like thick hairs. These are scraped off and the stem is then trimmed. The mushroom is cut into two or four pieces depending upon the size. The chanterelles and girolles are peeled, trimmed, and cut into bite-size pieces. All the mushrooms are blanched in boiling water for a couple of minutes and set aside until needed. Some are cut into smaller pieces to be used in farces, but many are sautéed in butter to be used as a garnish.

© 2001 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

The Auberge serves a roast pigeon dish — pigeonneau fermier d’Alsace rôti aux épices douces — that consists of a boneless pigeon with a small amount of liver stuffing and sweet spices. The pigeons arrive in the kitchen with their head and feet still attached. They’ve been eviscerated, but the liver, heart, and gizzard are still in place. Most of the feathers have been removed, but not all. This is facilitated by using a towel for traction on the small feathers. The feet are cut off and the wings are removed above the “drumette.” The skin and flesh are slit to the bone in the center of the back and breast, running from neck to tail. The bird is then deboned, leaving two boned halves. The liver is forced through a sieve to purée it. The purée is seasoned with a little salt and pepper and about half a teaspoon is stuffed between the breast meat and the skin. The inside of each pigeon half is seasoned with a spice mixture that contains just about every spice in the drawer — star anise, coriander seeds, cloves, nutmeg, white pepper, bay leaf, cinnamon, etc. The skin is then folded over and skewered together with toothpicks. The pigeon halves are browned and then roasted just before serving.

© 2001 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

To shuck a scallop at the Auberge, the shell is held with the flat side away from you. A large, flat-bladed, shucking knife is used to pry open the shell slightly. The tissue that is connected to the flat side of the shell is scraped off the shell. The flat shell is now released by the scallop, removed from the hinge, and discarded. The scallop, still in the other half of the shell, is allowed to rest a few minutes while the other scallop shells are opened in the same manner. When a scallop shell is opened, there’s a generous supply of sand found along with the scallop. The same flat knife is used to gently scrape the tissue, starting at the hinge, away from the shell. A lot of care is taken not to remove the scallop itself from the shell at this point. The thumb of the left hand presses the scallop against the shell so it is not disturbed. The other tissue is teased gently away from the shell and discarded. The knife is then used to separate the scallop from the small, white, fibrous muscle on the right edge of the scallop. The scallop is then gently scraped from the shell. Once all the scallops are removed from their shells, they are thoroughly washed in cold water. The scallops are placed on a perforated tray in pairs with their sloped edge against each other; as each scallop rests in the refrigerator, it takes on a more cylindrical shape. The scallops shucked this afternoon won’t be used until tomorrow at the earliest.

© 2001 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

To clean these small trout, the belly is slit open with a small knife from anus to gills. The body is gently squeezed to expel the intestines and other internal organs. Everything comes out easily except for the esophagus, or whatever it’s called, which has to be pulled extra hard to tear it out. The trout are then washed and drained on absorbent paper. The cleaned trout are dusted with flour and deep-fried for serving.

© 2001 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.

One of the standard sweets served at the end of a meal here is a rustic chocolate truffle. The center is a ganache made from couverture (67% cocoa), cream, and finely granulated sugar. The mixture is finished with a little butter. The ganache is piped in small dabs onto a paper lined baking sheet and refrigerated. The centers are covered with plain couverture and dipped in cocoa powder. One of the cooks and myself donned latex gloves to add the covering to the centers. He put some of the tempered couverture on his hands and rolled a couple of the ganache centers between his hands until the centers were coated. He then dropped the coated centers onto a half-size baking sheet that was lined with parchment and covered with cocoa powder. We had two sheets like this. When he had about a dozen truffles on one of his cocoa-covered baking sheets, I would switch sheets and make sure that each truffle was thoroughly covered with cocoa powder. I would then shake four or five at once between my hands to shake off any excess powder. When the chocolate had hardened enough, I transferred them to another baking sheet to harden further. This went on for about 1000 truffles — minus a few samples.

© 2001 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.