December 26, 2011

Amuse-Bouche

artichaut et mayonnaise

(artichoke and mayonnaise)

Artichokes are really an adult food. Their intense, earthy flavor is not something we pop out of the womb craving. The flavor is so strong it can effect everything else being eaten at the same time. And eating them can take a bit of patience when presented with the whole, immature flower. Not everyone wants to peel-and-dip their way through a meal.

Up until 1969, I wasn’t a big fan of artichokes. As a kid, they took too much work, and I always seemed to get the one with the worm. It was well-cooked, but it still was a worm. I needed a lot of dip to cover up the taste. When my mother served them with 1000-island dressing, I could cope, but with just melted butter, they just became greasy on top of distasteful.

In 1969, I was in my second year of college in Rochester, New York. (That’s not counting the year I spent in Las Cruces, New Mexico, that I had to repeat in Rochester.) I had moved off campus, and was lonely much of the time. On the return flight from the Bay Area at the end of the winter break, I meet a young couple with a small child. He was in his last year of dental school and she was a stay-at-home mom. We became friends, and I would spend three or four nights a week over at their house: either watching sports and drinking beer with him, or sitting around talking with her. We occasionally went out to eat together, and I often ate at their house. The relationship didn’t last past the end of the school term, when I dropped out of college. Although we all returned to the Bay Area, me in the south, and them in the north, we only got together once after that. It was a winter-to-summer relationship brought about by mutual “being away from home” but with no lasting depth.

One night in the late spring, Mrs. X, I no longer remember her name, served artichokes. Why is this significant? In Rochester in 1969, fresh vegetables were limited to a small variety and usually sold partially rotten and wrapped in plastic on Styrofoam trays. There was only one major supermarket in town that sold loose vegetables, but even there, the variety was limited. So the fact that Mrs. X obtained three, good-sized, perfect artichokes was a big deal. She didn’t just buy them, she knew what to do with them, too. She even had special artichoke plates. They were simple white plates with a depression in the center to hold the artichoke and a channel around the depression to hold the discarded leaves. The channel was interrupted in the front with another depression for holding melted butter.

It was with much pomp that Mrs. X served up that first course of artichokes, and I knew what to do. I removed each leaf and dipped the meaty end in the butter. I then used my front teeth to scrape the flesh from the leaf. Each leaf was then deposited, in order, in the channel, each one just overlapping the previous one. By the time I had worked my way down to the choke, there was a neat row of spent leaves circling the heart. I removed the choke with my knife and fork—no hands please—and cut the heart into quarters, each of which was dipped into the melted butter and then gobbled down. I not sure if I enjoyed that artichoke any more than others I had had by then, but I felt quite satisfied with my sophistication. I was sure that Emily Post would have been proud of me.

Come forward 31 years and I’m in Amondans, France, doing a stage at l’Château d’Amondans. The restaurant is celebrating its fifth anniversary and the chateau’s 250th anniversary. Various friends of Chef Frédéric Médigue, themselves all at the helm of Michelin-starred restaurants, contributed recipes, and sometimes talent, to the special anniversary meals. Pierre Gagnaire had sent a recipe for a starter along with his pastry chef to help with its preparation. The dish was a tartar of shrimp and langoustines marinated in passion fruit juice. Part of the garnish was slivers of artichoke hearts. There was also a creamy topping with fifty thousand ingredients which I didn’t find memorable. What I do remember is turning about 75 artichokes to harvest the hearts. By the end of the morning, my hands were stained dark brown. In the end, the dish was served without the artichoke-heart slivers because Chef Médigue didn’t like what they contributed to the whole flavor of the dish. Maybe the guests didn’t experience my artichokes, but I certainly became experienced at turning them.

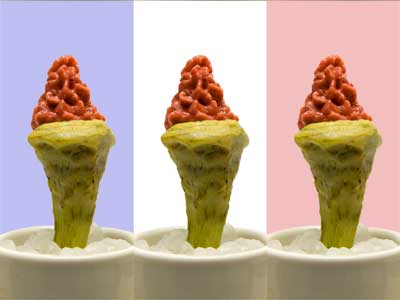

So recently when I saw some very small artichokes at my local farmer’s market, I thought about turning them to just reveal the hearts. Which is what I did. The stripped down hearts were blanched in boiling, salted water until barely tender, and then drained and chilled in my refrigerator. Rather than dipping the hearts in melted butter, I made some mayonnaise subversive, and seasoned it heavily with garum marsala and colored it very lightly with red coloring gel. I could have flavored the mayonnaise with just about anything: curry powder, chipotle powder, prickly ash, ketchup, etc. I piped the mayonnaise onto the tops of the artichoke hearts to turn them into flowers, or torches, or whatever you want to call them. The stems of the hearts were set into small bowls of rock salt to stabilize them in a vertical position. They could also be served in the dip, or in a number of other ways, but this is how I chose.

© 2011 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.