December 24, 2012

Mignardise

petite crème au chocolat blanc

(white-chocolate custard)

Out of control! That’s how I’ve often been described. I’ve been told that I need a filter for my mouth. I think about the cardboard sign that I had on my wall when I was in elementary school: “Be sure brain is engaged before putting mouth into gear.” Regrettably, I striped my gears a long time ago. I just seem to effect some people the wrong way. I don’t mean to, but it happens. (They’re just too sensitive.)

Maybe that’s why I like using methods that enforce control on the cooking process? I can’t overcook meat when I use my PID-controlled low-temperature cooking bath. Short ribs sit for 54 hours in 55 °C (131 °F) water and they come out pink and fork-tender. Possibly, that’s why I like to cook using a bain-marie? I know I can walk away and all will be fine.

Bain-maries have been around for a long time. Their first use was probably as a way of applying slow, moderate heat for alchemy. When they were first used for cooking isn’t written anywhere that I know of, but it was a long time ago.

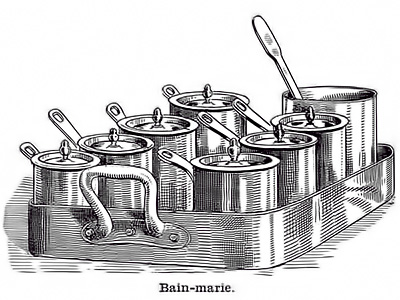

I generally see them used in two ways in cooking. The first as a shallow pan of water on a stove with other, smaller pots of sauces inside. The larger pot is filled with water that is kept just at a simmer. This keeps the contents of the smaller pots at the same temperature. The modern steam table is a variation of the concept.

The other form of a bain-marie is where a smaller pan in placed in a larger pan of hot water, and both are placed in an oven. This is a much newer form of a bain-marie. The water in the outer pan limits the temperature of the contents of the inner pan. This is a common way to control the cooking of custards and the like.

For the recipe below, which I found in the French cooking magazine Guide Cuisine in 1997, the individual ramekins with the uncooked custard are placed in a larger pan of hot water, and both are placed in the oven. In my condo, the hot water comes out of my tap at about 46 °C (115 °F). Twenty minutes or so later when the custards are removed from the oven and their water bath, the water temperature has risen to 80 °C (176 °F), warm enough to gently cook the custard and form a smooth mesh of proteins which feels good on your tongue.

In their usual form, proteins are linear polymer chains of amino acids bonded together by peptide bonds. Proteins are often visualized as coils that look like an old-fashioned telephone cord made from ribbon. A protein’s shape is held in place by bonds that keep it from unwinding. When the protein is denatured by adding heat, the bonds release, and the coil can unwind. As masses of these unwound proteins disperse through a liquid, an unconnected bond of one protein may join to that of another protein. In this manner, the proteins form a meshwork that traps liquid and increases the overall viscosity, and we have our finished custard.

If the mesh is heated too much, essentially overcooked, the custard will curdle and turn from a smooth, homogenous mass to scrambled eggs floating in liquid. The meshwork will literally tighten to the point that the trapped liquid is squeezed out. By using a bain-marie, this is easier to prevent because the time period that begins when the custard starts to be considered cooked and that ends when it begins to self-destruct is longer than if the ramekins just sat in the hot oven. Since the time is lengthened, the temperature profile within the ramekins is more horizontal and even.

1⁄2 t

vanilla extract

1 T

finely granulated sugar

165 ml (2⁄3 c)

whole milk

30 g (1 oz)

grated white chocolate, divided

1 extra-large

egg, beaten

1. Preheat oven to 170 °C (340 °F).

2. Combine the vanilla extract and the granulated sugar with the milk in a small saucepan. Stirring continuously, bring to a boil. Remove from heat, and whisk in 20 g (2⁄3 oz) of the grated white chocolate. When melted, whisk the mixture into the beaten egg. Divide between 30-ml (2-T) ramekins.

3. Place the ramekins in a larger pan with hot water halfway up the sides of the ramekins. Bake until firm in the center, about 20 minutes.

4. Remove ramekins from water bath, and set aside to cool. Refrigerate until ready to serve.

5. Just before serving, sprinkle the remaining grated white chocolate over the tops.

Yield: 6 servings.

© 2012 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.