April 22, 2013

Amuse-Bouche

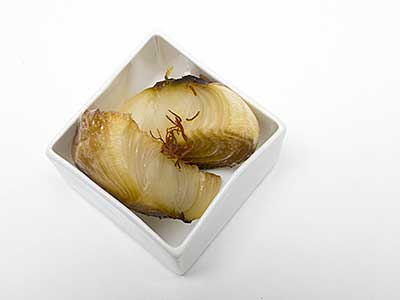

oignon rôti

(roast onion)

The smell was the first thing to alert me: vaguely biological, somewhat antiseptic, but mostly just obnoxious. At first, the source was simply a bundle of heavy-duty plastic which, being dirty and having been folded and unfolded many times, looked cracked and semi-opaque. The guy had pulled it from his trunk where it was buried under a pile of dirty clothes and miscellaneous car paraphernalia. While shuffling the package from hand to hand, he gently unwrapped it to reveal the foul smelling contents. It was one lobe of a human lung. Mostly white from having been preserved in formalin, the lung’s surface was covered with a dotted pattern of black spots. Looking closer, I saw that the spots were small globs of black, necrotic tissue.

The lung had been removed from a lifelong smoker. The guy holding it was a surgical resident from Stanford University and my current scoutmaster. My scout troop and I were in the campgrounds of the Pinnacles National Monument for a weekend camping trip. At fifteen, I had already been smoking for a couple of years, and Dr. Rosenberg was attempting to scare me into quitting. It didn’t work. Pending fatherhood, eleven years later, would accomplish that.

Besides the natural beauty of the park, one of the first to be set aside for preservation by the federal government in 1908, and the necrotic lung, one other event that weekend left an indelible impression on me. It was the first time I cut myself while cooking. Now, fifty years later, the quarter-inch size, semicircular scar on my left thumb is visible only under very bright light, and I can still feel a small crease in the skin where it didn’t perfectly mend. I still have the old BSA sheath knife that interrupted my cooking so many years ago.

My long-ago accident happened while I was dicing onions for some long-ago forgotten dish. (Maybe the lung had distracted me.) No one had shown me how to dice onions, but I had somehow evolved into the person in our troop who always did the cooking while others were out hiking. My cooking wasn’t complicated, and it wasn’t very good, but no one ever complained. When I realized what I had done, I wrapped my thumb tightly with a rag, and continued to work.

Upon learning of my misadventure, the scoutmaster⁄surgeon immediately got into his car and left the campgrounds. He didn’t say why he was going. He only said that he would be back as soon as he could.

About an hour later, he returned with a brown-paper bag and a newspaper. The newspaper was for him, and the paper bag was for me. Inside the bag was a narrow roll of gauze, a roll of white tape, and a brown-glass bottle. While he uncapped the bottle, I was instructed to remove my now-bloody bandaging. He held my thumb firmly, and told me that his next move would hurt. He then poured a generous amount of the clear liquid straight from the bottle over my still oozing thumb. The blood and the raw edges of the skin began to ferociously bubble. The blood washed away. My skin around the cut turned a sickly gray. The sting actually wasn’t that bad. He then dried my wound, bound it with gauze, and anchored it with tape. I found the whole process fascinating.

I relived the peroxide effect a year later when we dropped pieces of hamburger into flasks of hydrogen peroxide in chemistry class to demonstrate some principle or produce some gas. All I remember is the bits of burger vigorously bubbling away in the clear liquid. When the bubbling stopped, and our merry band of teenage chemists retrieved the burger bits, they appeared totally cooked. (Looking back, this may have been my first venture into Modernist cuisine.)

I still keep a bottle of hydrogen peroxide in my medicine cabinet to disinfect cuts, and onions have become my favorite vegetable. I’ve gotten pretty good at sculpting them into various shapes. Although I usually prepare onions as part of other dishes, there are occasions when I let them solo. This is one of those times. Here’s how I got the idea for this preparation.

There used to be an Italian-style restaurant on Alvarado Street in Monterey, California, that grilled halves of red onions over charcoal until the onions had softened and their edges were browned. They then let the charred onions cool in a bath of balsamic vinegar. I ate the onions many times in the 1980s before the now closed and forgotten restaurant took it off their menu. Then, years later, at the 2013 Winter Fancy Foods Show, at a booth marketing products from the Ibaraki Prefecture, I received a recipe for a grilled onion seasoned with awazuke soy sauce. I thought back to those balsamic-infused onions of thirty years ago.

At about this same time, I was given a small bottle of peach-flavored balsamic vinegar, and I found some good-looking cipollini onions at a local market. It was time to make an amuse-bouche reminiscent of those onions in Monterey.

Since cipollini onions have a squat shape, I trimmed them a bit differently than standard onions. I took a thin, flat slice from the stalk end to expose the onion flesh. Any adventitious roots were trimmed flat from the other end, but I left the main, central root structure intact. Finally, I removed the dried, skin-like outer layer.

I poured the vinegar onto a plate to the minimum depth that would just cover the surface, about 3 mm (1⁄8 in), placed the onions cut-side down in the vinegar, and left them to marinate for a few hours.

Later, I briefly drained the onions, but reserved the vinegar on the plate. I placed the onions root-end down, on a baking sheet, and roasted them in a hot oven [205 °C (400 °F)] until tender and slightly browned. Finally, I left the cooked onion halves to cool, cut side down, in the reserved vinegar.

To serve, I drained the onions well and cut them crosswise into two pieces. In the picture, the pair of onion pieces is decorated with a few saffron threads. A little very finely diced peach flesh would probably be a more fitting decoration for the onion pieces.

© 2013 Peter Hertzmann. All rights reserved.