After reading a slew of bœuf à la mode recipes for the preparation of last month’s article, I decided that I should do something that I’ve never done before, prepare bœuf à la mode. Yep, when it comes to bœuf à la mode, I am a virgin. But in this instance, unlike when I was a teenager, virginity is easily correctable.

First I had to choose a recipe from all those I had looked at when I was writing the article. I decided upon Joules Gouffé’s version for two reasons: It had sufficient detail without being overly complex, and I have found success in the past with other recipes in his Le Livre de cuisine.

Before I could cook this dish I had to obtain a special piece of equipment and a few special ingredients. I bought two sizes of larding needles for inserting strips of fat into the meat. The heavier one turned out to be better for the large piece of meat this recipe requires. After ordering the needles, I had to wait about three weeks for delivery before I could start cooking.

Although finding the meat was not a big issue, it was a big piece to buy. I bought a whole beef top sirloin butt (North American Meat Processors designation 184) that weighed in at about 5 kilograms (about 11 pounds). From this I cut two square portions of about 2 kilograms (about 41/2 pounds) each. I had about 500 grams (about 1 pound) of stew meat left over, and an equal amount of fat and trimmings to discard.

The pork back fat that I would need for larding is usually no problem, but my usual supplier was out of stock. I found another supplier who was able to provide some nice long pieces in a couple of days. Note that it is necessary that the piece of fat be long enough to stretch the full length of the piece of beef.

None of the other ingredients were a problem to obtain. They are items I normally have in my kitchen, so I went to the refrigerator and pantry when I started to cook my bœuf à la mode.

Gouffé says to cook the meat for 41/2 hours so I allowed 6 hours total to prepare the recipe. It turned out that I need only about 4 hours total.

I considered not larding the meat because the piece I had selected probably had better marbling than the meat available to Gouffé 140 years ago, but I decided to do so anyway. It was something that I had never done, and even some 21st-century recipes for bœuf à la mode still specify larding. The process involves inserting strips of pork back fat into the meat parallel to the grain.

To lard the meat, I chilled the back fat thoroughly and then cut it into long strips that were about 1-centimeter (0.4-inch) square. These were again set in the refrigerator to chill once more after cutting. Some books recommend placing the strips in ice-water; the goal is to harden the fat as much as possible. I was lazy and just used my refrigerator to keep them cold. I removed the strips one at a time from the refrigerator so the remainder would stay cold.

Using my larger larding needle, I inserted a strip of fat in the channel of the needle at the end opposite the handle and slid it down towards the handle. I pulled it out at the other end so the excess would be at the handle, not the tip. The fat near the tip stopped just behind the end of the bevel in the tip. I used a small, metal skewer to prod the fat to slide in the channel.

Once the needle was loaded, I inserted it into the meat and pushed it all the way in. The needle was shorter than the meat so it was necessary to push the meat up on the needle until a little of the white fat at the tip of the needle was visible. I then pushed the skewer through the end of the fat so I could hold it in place while I pulled the needle from the meat.

Next I reshaped the meat into its original form and centered the fat in the meat so there was an equal amount of excess sticking out at each end. I repeated this process until the whole piece of beef was larded. I attempted to place the fat strips about 5 centimeters (2 inches) apart. It took me a while to work out a routine for loading the needle and on a couple of insertions, the fat strip slid towards the handle when the needle was pushed through the meat. In these cases, I had to reload the needle with a new, colder piece of fat.

When the larding was complete, I tied the meat with heavy cotton string. I did not tie it very tightly as I would in making a rolled roast, but the string was just tight enough to hold the meat in shape. By tying the meat, it would be easier to handle the piece after cooking when the meat is quite fragile. Because the meat was cut initially into a piece that approximated a square, I only needed to tie it with two strings in each direction.

While I was larding and tying the meat, I blanched the beef foot. The butcher had already cut the foot into 5-centimeter (2-inch) long sections so that it would be easy to fit in the pot. The foot weighed about 500 grams (about 1 pound). To blanch them, I just placed the pieces in a saucepan and covered them with cold water. I brought this to a boil over high heat. I let it boil for about a minute and then drained it. Gouffé calls for the foot to be boned, but I used it with the bones, which would add more gelatin to the cooking liquid. Also, the pieces are much easier to bone after cooking for a few hours.

The meat was placed in the bottom of a 6-liter (6-quart) stock pot. To this I added the blanched beef-foot pieces, 500 milliliters (21/8 cups) dry white wine, 100 milliliters (7 tablespoons) cognac, 600 milliliters (21/2 cups) good quality chicken stock, 600 milliliters (21/2 cups) cold water, and 30 grams (1 ounce) coarse salt. I placed the pot over high heat to bring the contents to a boil.

While the pot was heating, I prepared the vegetables and solid flavorings. I peeled enough carrots to yield about 500 grams (about 1 pound). These I cut into 6-centimeter (23/8-inch) long pieces. The thicker pieces were also cut lengthwise in two. I trimmed and peeled a large onion, and cut it into quarters. The size of the onion pieces doesn’t matter because they will cook almost to mush in the time it takes for the meat to cook, and they will be discarded. I also set aside 3 cloves and a big pinch of black peppercorns. Finally I constructed a bouquet garni from 2 green onions, 1 bay leaf, 3 sprigs of flat-leaf parsley, and 3 large sprigs of thyme, tying them together with a piece of string.

When the liquid came to a boil, I skimmed the surface briefly with a small ladle. There was very little scum, probably because the foot had been blanched and the meat had essentially no surface fat. I only had to skim the liquid once during the entire cooking process.

After the skimming, the vegetables and solid flavorings were added next, the pot covered, and the liquid brought back to a boil. The meat was cooked slowly in barely boiling liquid. On my stove, that means lowering the heat in stages to what will eventually be at the lowest possible position. But if I turn it down to that point at the beginning, the food will stop cooking. I have to sneak up on it. I turned the knob down halfway and waited a few minutes. Then I turned it down another halfway and waited again. By the time I had washed all the equipment used during preparation (and read some of the morning newspaper), the knob was at its lowest setting and the liquid was quietly bubbling away below the cover.

(While the beef was cooking, I ran to the store to buy the boiling onions that I would need for the garnish and had previously forgotten to buy. I plan on about 5 onions per person.)

After 2 hours of cooking I checked the meat for the first time. I used a long meat fork to judge the doneness. It wasn’t ready yet, but it was obvious that it would not take the full 4 1/2 hours that Gouffé specified. Out of curiosity, I measured the temperature of the cooking liquid. It was about 95 °C (203 °F).

After 3 hours of bubbling away on the stove, I decided that the meat was cooked. I took the pot off the heat, and using a slotted spoon, removed the various components and placed them on separate plates, one for the meat, one for the foot, and one for the carrots. It was early in the afternoon and dinner was many hours off, so I decided to reheat the components later instead of attempting to keep them warm. I strained the cooking liquid through a chinois and discarded all the remaining solid ingredients separated from the broth.

I strained the broth a second time back into the stock pot, but not before I thoroughly rinsed it out. The pot was placed over high heat to bring the broth to the fullest possible boil. I reduced the broth by half. I tasted it and decided that no further seasoning was necessary. The broth was left in the pot, covered, off the heat. The plates with the other ingredients were covered with plastic wrap and left on the countertop.

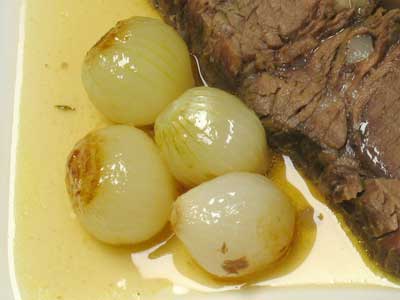

About 30 minutes before dinner time, I peeled the boiling onions and placed them in a saucepan along with 30 grams (2 tablespoons) of butter and enough water to barely cover them. The onions were in a single layer without much extra space. The uncovered saucepan was then placed over high heat. The liquid was brought to a full boil and kept there. The goal was to completely boil off the liquid. While this was happening, the onions cooked. When the liquid was exhausted, it was important to continually and gently stir the onions until they were browned a bit. Finally, I sprinkled a little salt over the onions and removed the saucepan from the heat. RECIPE

While the onions were cooking, I boned out the foot and placed the edible portions back into the broth along with the meat and carrots. The combination was brought to a boil. Then the heat was turned down just a bit, and after a few minutes, turned off completely.

When the onions were ready, I removed the meat, foot, and carrots from the pot with a slotted spoon for one last time. The strings were removed from the meat and discarded. I cut the meat into thick slices and arranged them on warmed serving plates. I cut the foot pieces into smaller pieces and added a few to each plate. I also arranged some carrots and onions on the plates. Finally, some of the broth was ladled over the meat, and the plates were served. RECIPE

The piece of meat I cooked would have easily served six people, even though there was just two of us that night. I awoke the next morning to a fair amount of leftover meat, carrots, and broth. (The refrigerator seemed to eat the leftover beef foot overnight.) Then I remembered another version of bœuf à la mode that I had discussed in the earlier article, one presented cold in aspic. When I reviewed that recipe I found that the ingredients were assembled in a mold and many more carrots would be required than I had on hand. But then I remembered the presentation with aspic that was done in my article on fromage de tête, and the night’s meal was determined.

I started by scraping off the fat that had congealed on the surface of the broth overnight in the refrigerator—there wasn’t much. The broth was a rather loose gelatin when chilled. I placed the now de-fatted broth in a saucepan. Then I cored and shredded a quarter head of cabbage, about 125 grams (about 1/4 pound), and added that to the saucepan. Finally, I beat an egg white and added that, stirred everything together, and placed the saucepan over high heat. While the mixture was coming to a boil, I set a strainer over a bowl and lined it with a piece of clean muslin. As the mixture came to a boil, I could see the liquid that bubbled up through the mat of floating cabbage initially cloud up with egg white, but then turn clear as the egg white with its captured impurities was trapped in the mass of cabbage. I removed the saucepan from the heat and slowly poured the liquid into the strainer. After a couple of minutes, I had a bowl of hot, clarified broth.

I knew from the earlier consistency of the cold broth that I would have to augment it with more gelatin. So I placed two sheets of gelatin into a glass of cold water to soften it. I poured out about 125 milliliters (1/2 cup) of the hot, clarified broth into a small pitcher. To this I added the gelatin sheets, which I had first drained. The broth was still hot enough so that the gelatin dissolved immediately, and my aspic was complete.

I cut a slice of the meat and placed it on a chilled serving plate. I also cut some carrots to garnish the meat and arranged them on the plate. Lastly I poured a thin layer of hot broth around the pieces on the plate. I then placed the plate in the refrigerator for ten minutes to chill and solidify the broth. After the first layer of broth was solid, I added a second layer. I didn’t pour just one thick layer in the beginning because the meat and carrots on the plate may have floated up and moved around. The purpose of the first layer was to “glue” everything to the plate. The purpose of the second layer was to bring the height of the aspic to the desired level. The finished plate would make a nice entrée (first course) or a light supper when accompanied by a small salad. RECIPE

After eating the complete bœuf à la mode in two different forms, one question still remained: Is it really necessary to lard the meat? After all, modern cattle are grown to produce a better distribution of fat in the meat than their ancient brethren. This distribution of fat should produce a moister result without needing to add fat to the meat. I also wondered how fat in one portion of a muscle could redistribute to other portions of the muscle. Because I still had the other square piece of meat that I had cut from the original top sirloin butt, it was simple to just duplicate the recipe without the larding. The result was surprising: The meat required an extra hour of cooking until it felt tender when I pierced it with a fork, but it was close to falling apart by then. The taste of the meat when served seemed to be the same, but maybe the meat was a little tougher—but only maybe. I think that the next time I make this dish, whether I lard or not will be more an issue of having the larding fat on hand rather than a definite requirement to lard. Either way, the flavor of bœuf à la mode definitely makes this a worthwhile dish to prepare another time.